This post is about pathfinder, a GPU vector graphics renderer written in Rust by Patrick Walton as part of his work in the emerging technologies team at Mozilla. While I have followed this work very closely, I have contributed very little code to pathfinder so the credit really goes to Patrick.

If you've read other entries on the blog you've heard of lyon, which helps you with rendering vector graphics on the GPU by turning paths into triangle meshes. Pathfinder takes a completely different approach, so you should ignore everything I have written about lyon's tessellator while reading this post.

Also, Pathfinder has gone through several complete rewrites each of which going for very different approaches, so information on some of Patrick's older blog posts doesn't apply anymore.

Pathfinder can be used to render glyph atlases and larger scenes such as SVG paths. The two use cases are handled a bit differently and in this post I will be focusing on the latter.

Tiling

Pathfinder splits paths into 16x16 pixels tiles. This tiling scheme has the following purposes: - Decompose the path which as a whole is a very complex object to render, into may smaller and simpler objects. - Use tiles that are completely filled with an opaque pattern for occlusion culling.

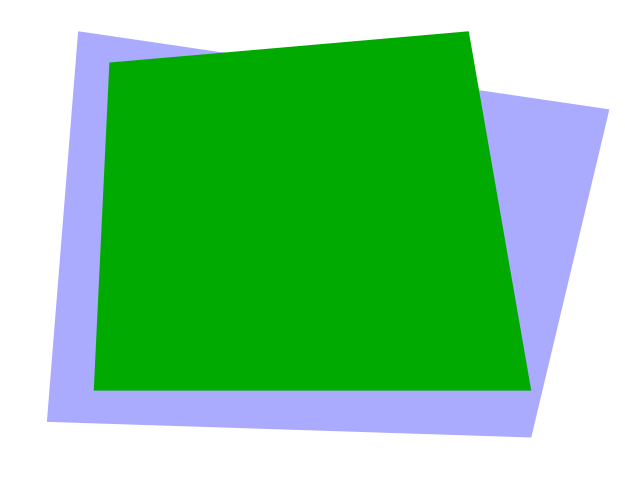

For example let's look at the following simple scene:

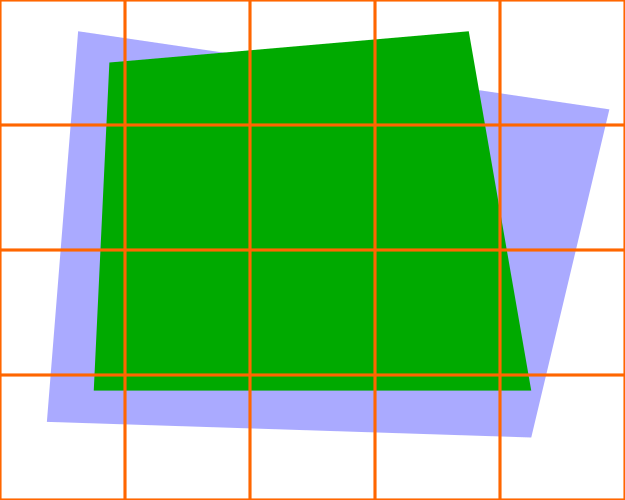

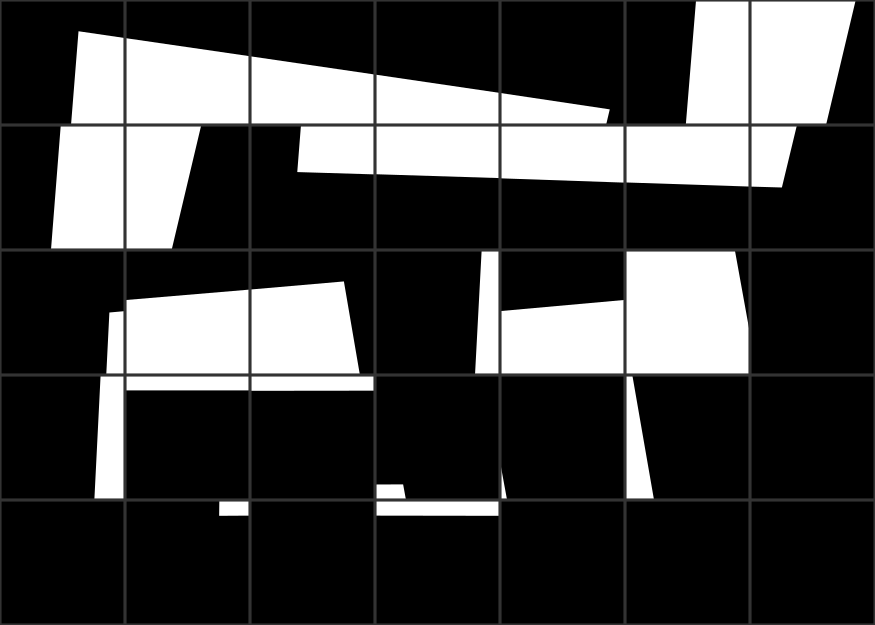

And decompose it into tiles:

In the scene, we have a number of opaque tiles that are very simple to render once we have identified that they are fully covered by a path.

These are simply rendered by submitting a batch of instanced quads.

A very good property of opaque tiles is that they completely hide what's under them, so we can trivially discard all blue tiles below an opaque green tile since we know it is fully occluded. This massively reduces overdraw in typical SVG drawings.

The image below gives an idea of the overdraw of the famous GhostScript tiger. The lighter a pixel is, the more times it is written to with a traditional back to front rendering algorithm without occlusion culling.

Because memory bandwidth is often the bottleneck when rendering vector graphics (especially at high resolutions), this occlusion culling is key to pathfinder's performance.

Here is a view of the opaque tile pass for the GhostScript tiger in renderdoc:

The opaque tile pass is very fast because it has zero overdraw and doesn't need any blending.

Alpha tiles

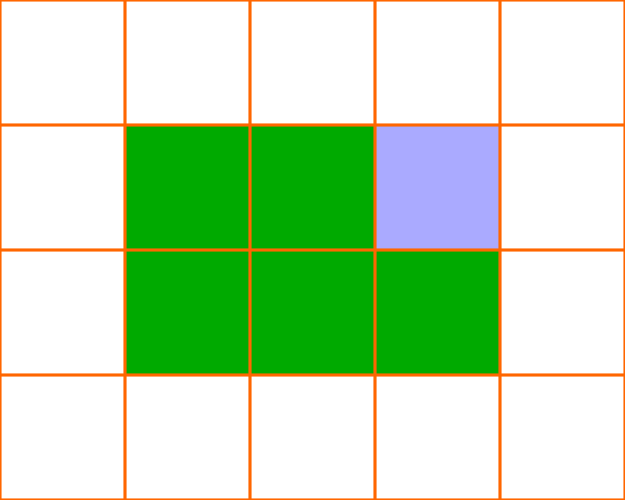

Back to our simple scene, this leaves us with the partially covered tiles to deal with:

Opaque tiles are easy. It's good that we were able to detect them and render them with simple instanced quads, it even gives us a crude approximation of the final image, but the real challenge remains to render curves with high quality anti-aliasing.

I will use the terms alpha tiles or mask tiles for tiles that contain edges. These are rendered in two passes. First a mask is generated in a float texture and the mask is used to render the tile on top of the opaque tiles.

The float texture containing the masks for our simple scene might look something like this:

Rendering the masks

It is very common when dealing with vector graphics to separate the computation of coverage (whether a pixel is in or out of the path) shading (color of the pixel if it is covered). Stencil-and-cover rendering approaches are textbook examples of this, traditionally rendering triangle fans into the stencil buffer to produce a binary coverage mask (pixels are either in or out of the path). Because this doesn't let you express partial coverage per pixel, anti-aliasing is usually done using multi-sampling.

Unfortunately, MSAA is quite slow on Intel integrated GPUs. Even on more powerful NVidia and AMD GPUs, MSAA is expensive with high sample counts, so people will rarely ask for more than 8 samples per pixel which provides something far from what I would call high quality anti-aliasing.

Instead of rendering masks into an integer textures like the stencil buffer, pathfinder renders into a float texture and uses instanced quads instead of building triangle fans along the shape of the path.

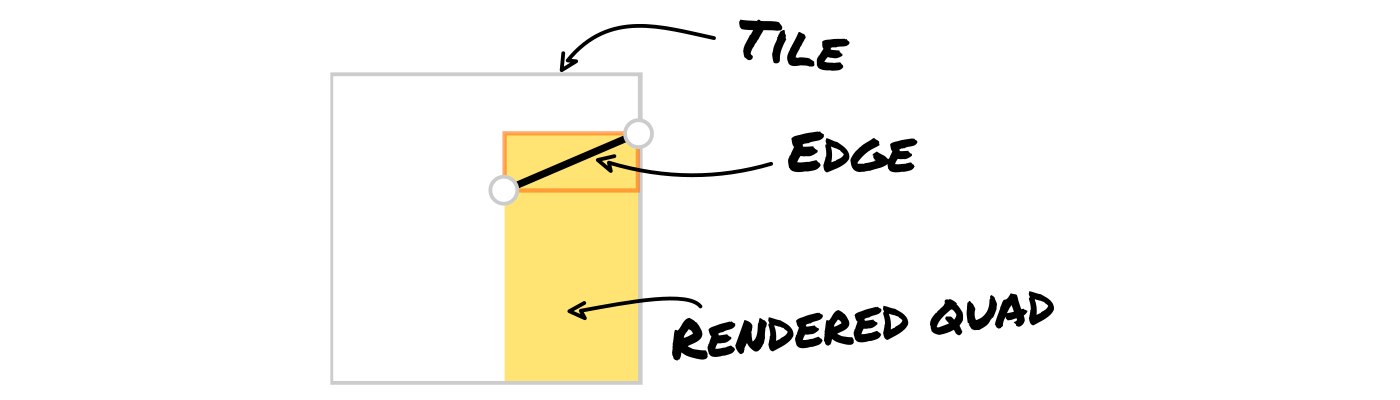

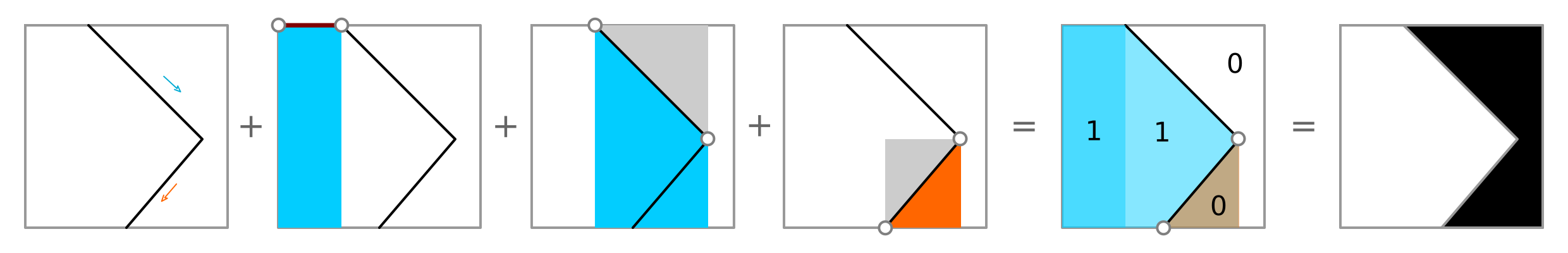

Each edge intersecting a tile is submitted as a quad that corresponds the bounding rectangle of the edge intersected with bounds of the tile and with the lower edge snapped to the bottom of the tile.

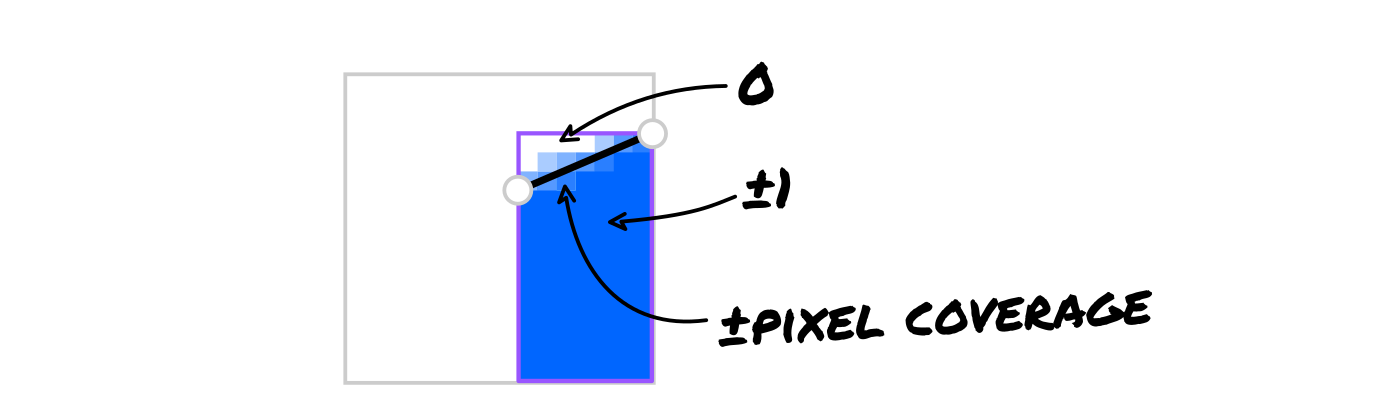

That the shape of these quads might look somewhat arbitrary. Before we can make sense of it we have to look at what this quad actually renders. For each pixel the fragment shader writes 0 if it is fully above the edge, ±1 below the edge, or a value in between corresponding to the coverage of the pixel if it is near the edge. The output value is either positive or negative depending on the winding of the edge.

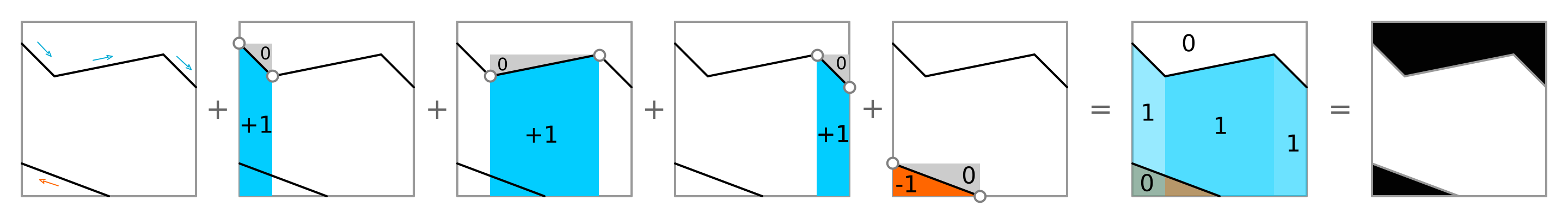

The quads are rendered with additive blending, causing the contributions of each edge to accumulate in the tile's mask.

Now why did we snap the bottom of the quads to the bottom of the tile?

In a lot of vector graphics rendering approaches, it helps to imagine that we are casting a ray (usually horizontal) coming from far away and looking at intersections against the path to generate a winding number for each pixel along the ray.

In pathfinder, the edge quads are equivalent to groups of vertical rays coming from the top of the tile, writing the contribution of a single edge to all pixels below the edge, down to the bottom of the tile. We could have also snapped the top of the quad the top of the tile, but since we don't need to consider pixels above the edge we save a few pixel's worth of work by only stating at the top of the edge's bounding box.

Rather than only writing the winding number between edges, pathfinder simply writes the contribution of each edge to all pixels below it, which will give the same result since the contribution of two edges can cancel each other out if our imaginary ray was going in then out of the path before reaching the pixel.

Note that using vertical rays is purely a matter of convention. Pathfinder could have been written in a way that follows the "horizontal ray coming from the left" analogy by snapping the right side of the quad to the right of the tile.

What if the top of a tile starts is already inside of the path ?

In the previous illustration we took it from granted that the top of the tile was outside ( initial winding numbers are zeros), but this does not always hold true in practice as any edge above the tile can contribute as well.

One solution could be to simply include all edges above the tile but for large drawing this can bring a lot of edges. So pathfinder handles this during the tiling phase on the CPU by tracking the winding number at the top of each tile and inserting a minimal amount of extra edges to compensate for the information that is lost by only considering edges inside of the tile.

On the left side of the image below, the tiger is rendered and the triangles emitted during the compositing pass of the mask tiles are highlighted in yellow. On the right side the same pass is rendered on top of a black background to better see which parts of the drawing end up drawn with mask tiles. The image was produced thanks to renderdoc.

Summary

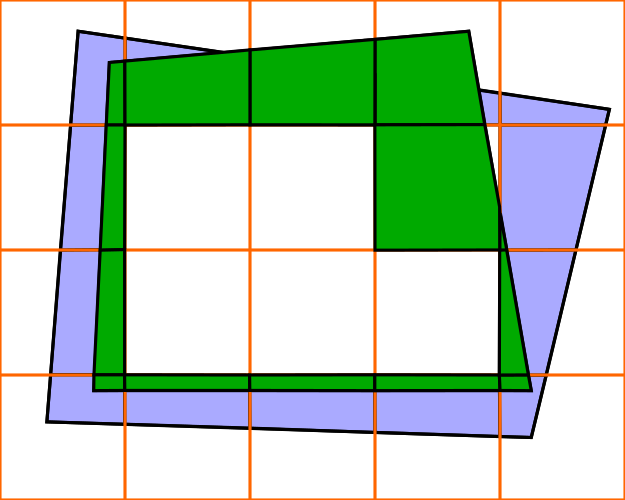

Piecing it all together:

- Paths are split into tiles on the CPU.

- Mask tiles are rendered in a float texture on the GPU.

- Solid tiles, which were detected during the tiling phase, are rendered into the destination color target.

- Mask tiles are composited into the color target, reading from the mask tiles that were rendered in the float texture.

The above sequence is what happens under the simplest settings. Pathfinder has the option to start submitting rendering commands while tiling is in progress to hide some of the latency of the tiling phase. There is also the option of tiling paths in parallel using rayon, which provides a nice speedup on computers with more than two physical cores.

Rendering strokes

Up to this point I only wrote about filling paths, but strokes are also important. Currently pathfinder simply transforms stroke primitives into fill primitives on the CPU. It works and was a quick way to get things up and running, but it's certainly costly. Rendering strokes without expressing them as fills will be implemented eventually. The strokes can generate mask tiles just like fills. The main difference would be in how these mask tiles are generated. With round line joins and round line caps it's pretty simple. We can use the maximum of the distance to each edge. Other line joins require a bit more work but there is a lot of prior art to follow or get inspiration from.

Rendering other types of primitives

Pathfinder's tiling scheme has the following nice properties:

- Mask tiles can be rendered in any order.

- The "compositing" phase is independent from how the mask tiles were generated.

This means that any kind of rendering primitive (2D distance fields come to mind for example) that can produce tile masks are very easy to integrate into this system without introducing batching issues, while also benefiting from the occlusion culling optimizations.

Rendering text

To some, pathfinder is better known as a text rasterizer than as a way to render larger vector graphics scenes. Rendering glyphs works the same way except that tiling isn't necessary because glyphs are usually small enough that the occlusion culling would not help at all.

Conclusion

Pathfinder's main takeaways are:

- A tiling scheme allowing powerful optimizations such as occlusion culling and a very fast opaque tile pass.

- An interesting way to compute coverage by rendering quads into a floating point texture.

The two are actually completely independent and one could use the same tiling approach while rendering tiles in a totally different way for example using multi-sampling instead of computing coverage analytically (There is an open issue about adding an option for that in pathfinder). I really like the composability of this architecture.

Pathfinder is a very simple, pragmatic, yet fast approach to rendering vector graphics using the GPU. It's not finished, there are many missing features and areas in which it can and will improve. I mentioned rendering strokes, and I think that the performance of the CPU tiling pass could be improved. In its current state it is still a good deal faster at rendering very large and complex SVG drawings than using a CPU rasterizer and uploading the result to a texture.

I'm hoping to integrate it in WebRender and start using it in Firefox some time this year. This is possible thanks to pathfinder's reliance on very few GPU features (any GPU supporting float textures works with pathfinder).

Is Pathfinder the fastest GPU vector graphics approach that there is? Probably not. It picks, however, the right trade-offs to be a very good, if not the best, candidate to my knowledge for integration in a web browser with a small rendering team and a very diverse user base (lots of old hardware to support).

I'll close this post with a few good reads for those who want to further explore different approaches to rendering vector graphics on the GPU:

- A presentation of Piet-metal by Raph Levien.

- GPU text rendering with vector textures by Will Dobbie.

- Random access vector graphics paper by Hugues Hoppe and Diego Nehab.

- Massively parallel vector graphics paper by Francisco Ganacim, Rodolfo S. Lima, Luiz Henrique de Figueiredo and Diego Nehab which follows up on the random access paper with a different data structure.

- FastUIDraw technical details part 1 and part 2 and XDC2016 talk.

- Easy scalable text rendering on the GPU by Evan Wallace.