Raph Levien recently published A crate I want: 2d graphics on his blog, which started some interesting discussions on reddit. At the same time there is a nascent discussion on the draw2d repository (which doesn't have any code at this point) about a potential 2d graphics crate.

These discussions contain a lot of interesting comments. One notable thing is that "2d graphics" means different things to different people. Some people want to render UIs, some people want to make games with rich vector graphics, some people want to be able to render complex but static SVG documents, some people want something designed for modern GPUs, some people want a library that can be used without a GPU, some want it low level, other want it high level, et caetera. Having worked with and on different approaches to 2d graphics rendering, I am convinced that 2d graphics isn't a single problem with an established solution, but rather collection of different problems which are best solved with very different solutions.

Because of that I would like this discussion to branch into several specific topics. In this post I'll talk about 2d graphics for the web and for user interfaces (a case could be made about separating the two of course), to a large extent with the intent to underline how specific the needs of these use cases are. Before I do that I'll write a few words about "canvas-like" graphics APIs.

Canvas, Cairo, Skia, QPainter - The immediate mode painting model

A lot of the most common 2d graphics APIs look somewhat similar: We have a context object which holds various drawing states like the current transform, pattern, or clip, we have a way to describe paths in post-script fashion (for example context.move_to, context.line_to, or if we are lucky, actual path objects that can be retained and reused). The general mental model is that you specify each drawing operation in back to front order and pixels are being painted immediately at each operation (or this is what the API pretends) but in practice drawing might be deferred so that the underlying implementation can take advantage of knowing about all of the elements and perform some global optimizations. For example CPU backends tend paint each drawing command individually, but GPU implementations pretty much need to be able to perform global optimizations in order to get acceptable performance. Another important aspect of these APIs is that they don't retain a description of the scene, which means that in order to render interactive content, you will submit the commands again each frame with some modifications for the parts that are changing. A common optimization when using this drawing model is for the user to track which region of the final image has changed and only redraw that part (in Firefox we call it invalidation).

Generally, implementing an efficient GPU backend for a pre-existing canvas-like API has proven to be difficult (doable but difficult). A lot of these APIs were designed before GPUs existed or became what they are now, and often a lot of expensive transformations need to happen between the API and the underlying GPU command submissions.

Compositors

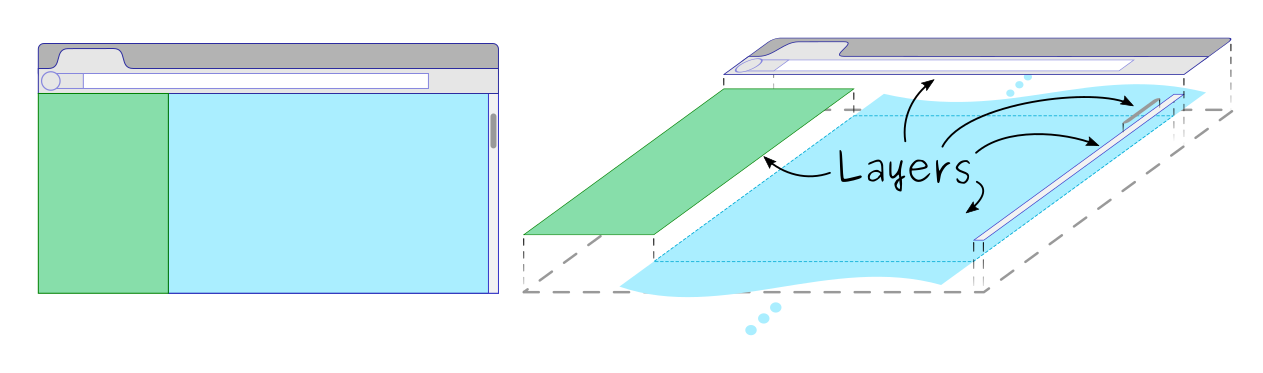

When motion comes into play (through animations or scrolling), re-rendering rectangles, paths, text and whatever else is moving at a high frame rate can become expensive with these drawing models. A very common solution to this problem is to group elements that tend to move together and paint them into retained surfaces that are often called layers (at least in the world of web browsers). Scrolling then becomes a matter of moving one or several layers and compositing them together to form the resulting image. This compositing operation is the job of... the compositor. Compositing within an application is very similar to compositing for a window manager, to the point where all modern window managers now provide APIs to let applications delegate the work of compositing their layers to the window manager, which avoids one compositing step, saves cycles, memory bandwidth and power. It is somewhat painful that all platforms expose this functionality in subtly different ways, but I think that it would be a mistake for any new UI toolkit to ignore it if they have a concept of retained surfaces.

Rendering web pages and UIs

By now I already gave away some of the details about how a lot of web browsers and UI toolkits work: an immediate mode painting abstraction, on top of which an invalidation system and a compositor were implemented to paper over the difficulty of rendering at 60 frames per second (without draining too much power). This is pretty much how Firefox (and most other browsers), Gtk and Qt have been historically approaching 2d graphics. This model is also to some extent something that Firefox, Gtk and Qt have or are in the process of going away from. I'll get to that in a moment, but before that I want to look at what drawing primitives are important for a web browser and a UI toolkit:

- Text. Oh text. Text is of course very important in this context and must have a particular look in each platform because a lot of users are bothered when hinting or anti-aliasing in an app doesn't match the look of the rest of the platform. In practice this means a lot of graphics libraries go through great lengths and pain to use the font rendering system of each platform they support. Text is hard. I wont get into these details but the people who implement the myriad of things that happen between loading a font file and the letters of this blog post showing up on your screen are heroes (no self-congratulations, I only touched very small portions of that). Patrick Walton is working on the font-kit crate which will hopefully erase some of the pain of dealing with font on each platform. I haven't used it yet but it's something to keep an eye on. Unless you are on a very high dpi screen, sub-pixel positioning and anti-aliasing make text a lot easier and nicer to read. One might decide to only target high dpi displays and punt on these features, but I wouldn't call that an easy decision and it will rule out some use case for sure.

- Simple shapes: mostly axis aligned rectangles and rounded rectangles, filled and their outlines.

- Very complex clipping scenarios: That one might not be necessary for some UI toolkits, but I'll mention it because clipping is a hard problem when your job is to render web pages. In any case it took quite a bit of trial and error to get that work with all use cases in WebRender.

- A few effects like drop shadows and blurs.

Notice how I didn't mention arbitrary paths? Of course these need to be implemented in a web browser but without them you can already render a large portion of the web. Any modern UI toolkit also needs to render arbitrary vector graphics to provide resolution independent icons and some types of UI widgets, but the need doesn't compare to the heaps of rectangles and text that compose UIs and web pages. Since you still need to support both arbitrary vector graphics and these specific simple shapes, you can simply focus on rendering the complex cases and you'll get the simple case for free, right? Except that in doing so, by not making the overwhelmingly most common case a first class citizen of the system a lot of potential for performance optimization would be lost. Today, WebRender doesn't know how to render arbitrary shapes. It's main primitives are (rounded) rectangles and more complex shapes just go through a fall-back mechanism that is part of Gecko and provides WebRender with the resulting content already rasterized. We'll eventually implement path rendering on the GPU but the current situation is good enough for us to ship WebRender first with the fall-back. My understanding is that the situation is similar with Gsk (Gtk's next generation rendering infrastructure): arbitrary vector graphics are rasterized using Cairo on the CPU while great care goes into rasterizing rectangles on the GPU.

Interestingly, for a lot of people path rendering is the central theme when thinking about 2d graphics. My point isn't to state what features are more important than others for a 2d graphics library, but really to stress how different the use cases are and that Rust does not need a single 2d graphics crate, but several, each with different goals and trade-offs.

Speaking of focus, I will now attempt to get my chaotic train of thought together and come back to the topic of web pages and UI toolkit I was writing about a few lines earlier.

Animation

I already mentioned motion. It is important enough that browsers and UI toolkits went from a simple "draw each element directly into the pixels of the window" model to embedding a compositor and/or relying on the window manager's compositor to accelerate moving things around. In my opinion, not taking motion/animation into account is one of the biggest mistakes a new graphics API design can make in he context of UIs (and in many other use cases). Frame N+1 is usually very similar to frame N, and taking advantage of this is key to get good performance and battery usage in rich and interactive experiences. There are different ways in which two frames can be similar. For example a few elements could be added, or all elements could exist in the two frames with different positions. For some APIs the latter might be considered as being two totally different scenes because all elements have changed, for other APIs that retain the structure of the scene it could just be thought of as the same frame with a different array of animation parameters. Whether the latter is superior to the former really depends on what you think the common use cases will be what is worth optimizing for. WebRender treats updates with several levels of priority. Scrolling for example must be able to operate at 60 frames per second, some larger changes to the structure of the scene can be more expensive to operate and are being carried asynchronously to ensure scrolling remains smooth. This is one of the many solutions to the common problem of having to deal with operations that could blow the frame budget. Another way could be to allow expensive work to be done asynchronously by users of the API prior to submitting rendering instructions. In any case I think that it is important to identify these bottlenecks and design the system in a way that prevents them from hurting frame rate.

In term of API, WebRender is much higher level than a traditional canvas-like API. Instead of building a single frame by submitting drawing commands, consumers of the API build a retained representation made of nested "display lists", and several frames will be rendered from this representation when animated properties of these display lists change (for example scrolling, or other types of animations). By squinting really hard one might see the display list building API as a sort of canvas-like API that builds a scene instead of an image, with an added notion of animated properties. But the display list building API itself doesn't have the generalist and flexible graphics API look of a Cairo or a Skia, instead focusing on describing positioned CSS primitives.

Wrapping up

At this point my plan was to delve into how WebRender approaches rendering on the GPU in more details and explain in what ways it fundamentally differs from Firefox's previous approach, but I already wrote too many words for a single post. To be honest, I think that WebRender already has the potential to fill the UI rendering niche. Some useful features are missing (for example a full software fallback), but these features are wanted in the long term anyway, so better add them (pull requests are welcome!) than try to replicate the colossal amount of effort that already went into the project.

Let this post be about me trying to convince you that rendering UIs comes with very specific design constraints and requirements, and that other niches which I failed to talk about would benefit from very different solutions. Whenever I have time to sit down and write another post I'll try to explain what I think would be a good direction for an hypothetical low-level crate focused on path rendering on the GPU with an eye for complex and dynamic scenes. Something very different in goal and scope from WebRender (and in some ways complementary). My hope is that I can stir some of the potential "Let's get together and make a 2d graphics crate" vibe towards that vision.