This post is about lyon, a rust crate to tessellate arbitrary 2D shapes into triangle meshes that can be easily rendered on the GPU.

About a year ago, in the lyon in 2018 post on this blog, I mentioned that I was working on a complete rewrite of lyon's central piece, the fill tessellator. I have been working on this for quite a bit. The work-in-progress pull request was created in February 2018. Almost two years in the making, this work made it in version 0.15, the project's biggest release ever.

It was a lot of work. Too much work. Fortunately, I am pretty happy about the result.

Motivation

So, why put so much effort in rewriting all of this?

Robustness

The fill tessellator was pretty robust, but not 100% bullet-proof. There's a built-in fuzzer in the test suite that could run for many hours before finding a shape that breaks the tessellator, but would always eventually stumble upon unrecoverable state and panic or return an error. The fuzzer wasn't the only entity to find issues. a few users reported some panics using the tessellator. Some of these reports were easy to address, some were very hard, and it almost always boiled down to precision loss introduced by arithmetic operations performed when detecting and handling self-intersecting geometry. The tessellator's algorithm had been built around a simplified mental model where arithmetic is precise, and key geometric properties could always be taken for granted. Long story short, there were some rare but very hard to fix bugs that required rethinking core parts of the algorithm.

The new tessellator embraces the idea that no matter how hard we try to avoid it, some floating point precision issues will eventually cause some invalid states to appear. Instead of relying on this to be prevented the new algorithm is built around being able to detect and recover from these issues.

This is done by splitting each iteration in two phases: the scan phase has most of the interesting logic of the algorithm, but doesn't perform any mutation. Instead it records changes that will be applied int the update phase which only performs the mutations.

Errors can be detected during the scan phase. Sometimes these errors imply that some of the analysis performed during the scan is invalid (for example due to incorrect edge ordering), but it doesn't matter because the scan phase hasn't committed any mutation, so we can bail out of it, do our best to sanitize our initial state and run the iteration again.

In overly-simplified Rust pseudo-code, the main loop looks somewhat like this:

impl Tesselator {

fn algorithm(&mut self) -> TessellationResult {

// ...

for iteration in self.iterations {

// Invalid states can be detected during the "analysis" or "scan" phase.

let updates = match self.scan_phase(iteration) {

Ok(updates) => updates,

Err(error) {

// Something is wrong, recover from it before trying again.

self.recover_from_error(error);

// Return an error if we fail the second time.

self.scan_phase(iteration)?

}

};

// Internal mutations can only happen here.

self.update_phase(updates);

}

// ...

}

}

This doesn't sound like much but it is a major shift in how the algorithm is organized. This alone required a rewrite and it paid off.

Another key aspect of the new design was avoiding to rely on prior events when information can be reconstructed locally. In other words try hard not to have invalid state accumulate and contaminate subsequent steps of the algorithm.

I am sure that bugs will be found as it always goes with any new non-trivial piece of code. It'll be wise to take the claims I made about robustness with a grain of salt until the code has had a chance to be used in more places and pass the test of time. I have let the fuzzer run on 4 of cores of a beefy desktop for about 48 hours and it didn't find any panic. That's already a lot more robust than the previous tessellator, at least with the family of bugs that the fuzzer is good at finding. I am also confident that it will be much easier to fix upcoming issues with the new algorithm.

Getting rid of fixed-point numbers

In an effort to make reasoning about precision easier, the old tessellator had moved most (but not all) of its geometric calculations to a fixed point number representation. It helped at first but in the long run it turned out to be a mistake. A mistake that was impossible to come back from after months of adjusting thresholds and other knobs to paper over precision issues that still existed. Fixed-point numbers, while providing a somewhat consistent precision loss that I had an easier time wrapping my head around, still lost precision and didn't solve the root of the issue. They helped with the easy problems and got in the way of fixing the hardest ones.

In addition, fixed point numbers came with two major drawbacks:

- The range of numbers that could represented inside the tessellator was greatly reduced in comparison with 32 bit floats. My initial feeling was that users wouldn't often need to work with coordinates larger than

32767.0, but that assumption proved to be wrong. While it was possible to work around the issue by scaling the path down and scaling the output mesh back up, it was far from a satisfying answer. - The vertices generated by the tessellator were almost but not quite the same as the points of the input shapes, due to being converted to fixed-point and back to float.

The new tessellator internally works with 32 bit floating point numbers and the positions from the original path are now unmodified in the output.

Custom vertex attributes

In order to achieve certain effects it is often desirable to be able to associate extra attributes per-vertex attributes, for example color, texture coordinates, bone weights, etc.

This has been lyon's most requested feature, but a tricky one to get right. On the surface it seems simple: give all path endpoints their own ID and present these IDs when building the vertices during tessellation. However the tessellator occasionally has to create new vertices that do not correspond to existing endpoints of the input path, for example when handling self-intersections or when flattening bézier curves.

To address this, the tessellator keeps track for each vertex of all of the edges that it belongs to and where on these edges. This information can be cumbersome to consume, so a concept of interpolated attributes was built on top of it. The idea is that an array of floating point numbers can be associated to each of the input path's endpoints and passed to the geometry builder when generating vertices. When the source of a vertex is more complex than a single endpoint, the tessellator interpolates the values automatically.

Find out more about this in the documentation.

The same mechanism was also added to the stroke tessellator.

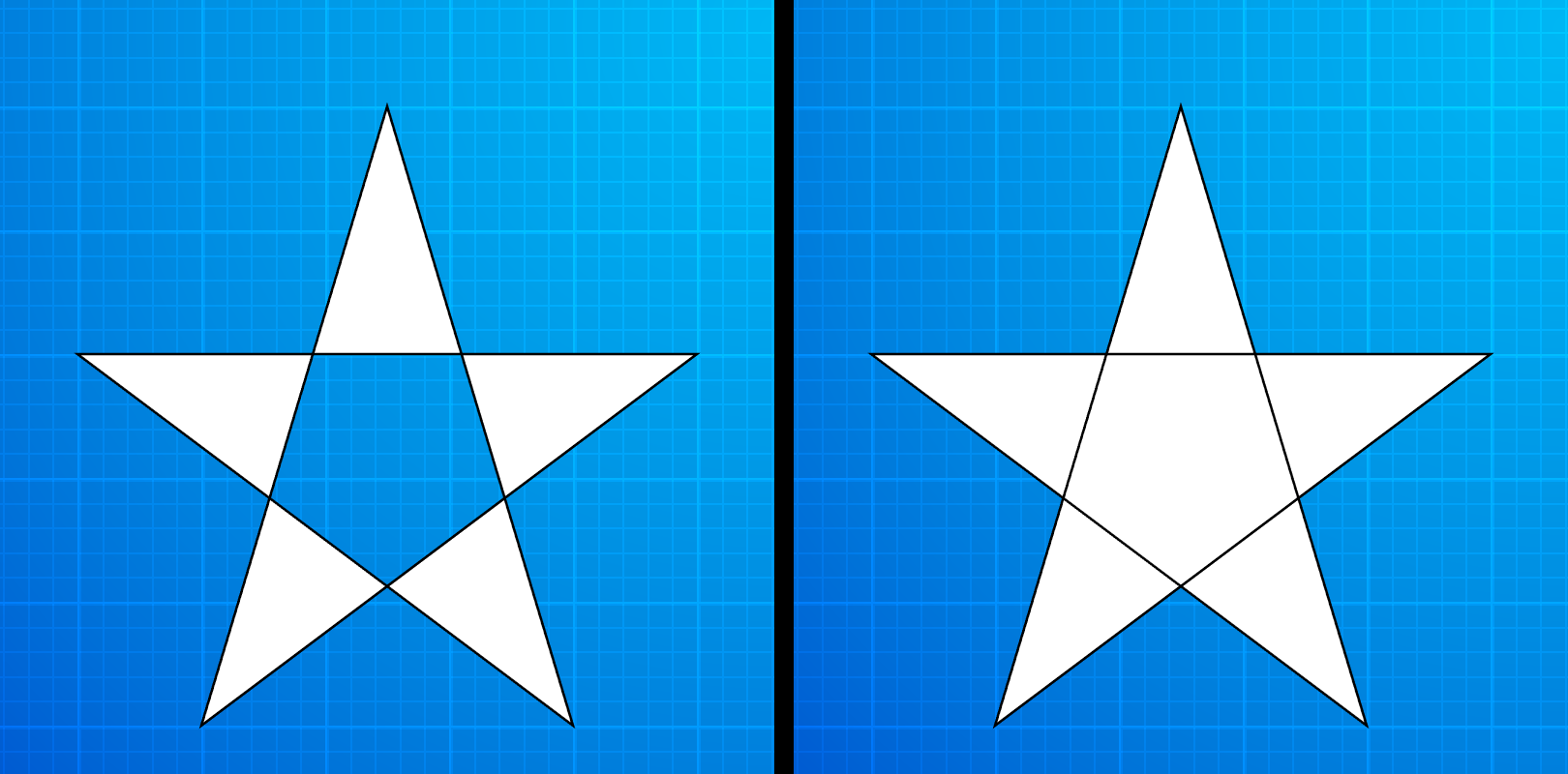

Fill rules

The old tessellator was pretty much written for the even-odd fill rule and adding more fill rules turned out to be difficult in hindsight. The new tessellator's algorithms was designed with this in mind and currently supports non-zero and even-odd. More fill rules can easily be added, but these two are the only ones in SVG standard.

The image below shows the same path, filled with the even-odd (on the left) and non-zero (on the right) fill rules

Other goodies

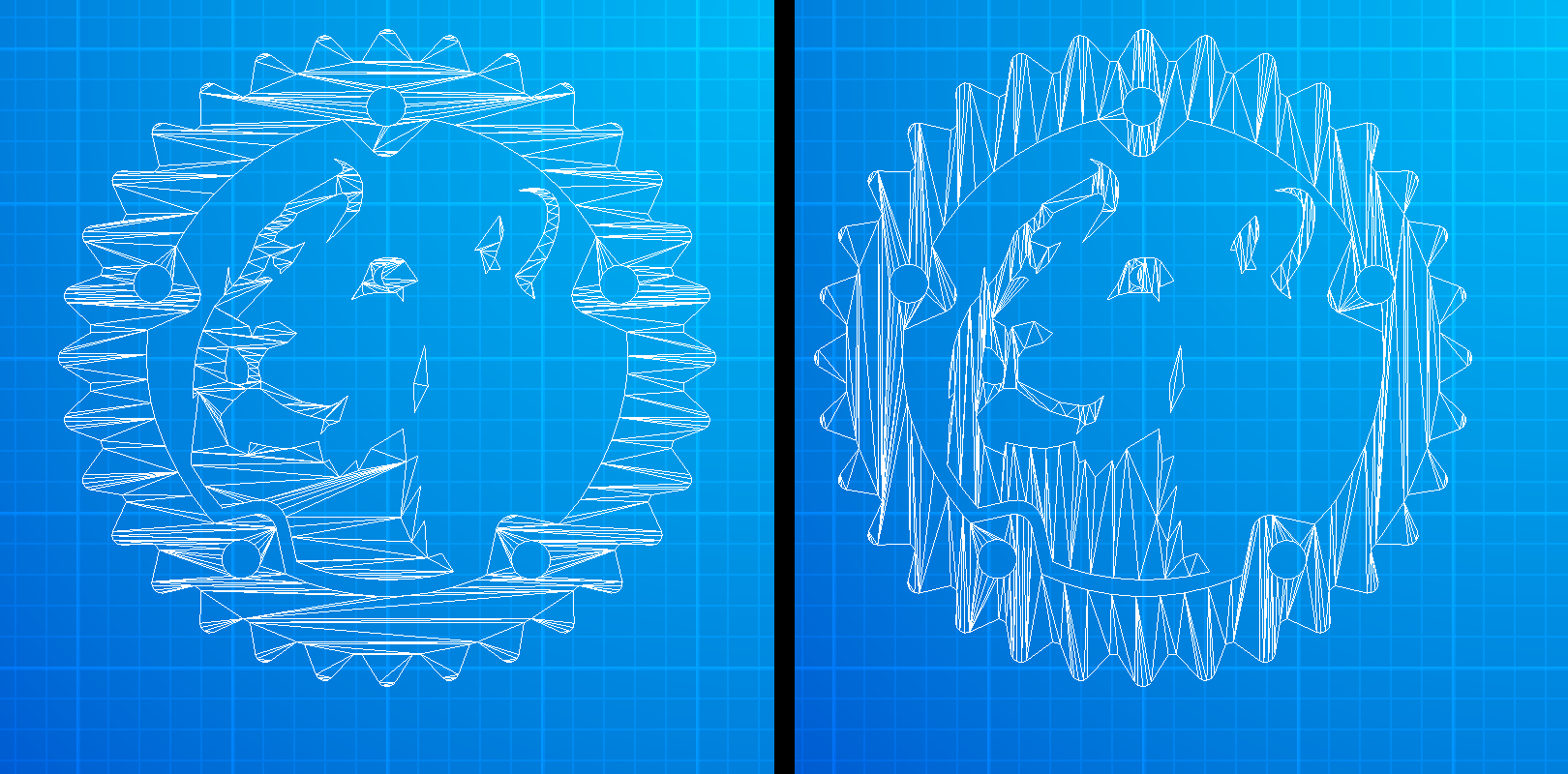

The new tessellator can dynamically chose to traverse the geometry vertically or horizontally. As a rule of thumb it is usually better for performance to do a vertical sweep for shapes that are taller than wide, and do an horizontal sweep for shapes that are wider than tall.

The image below shows the triangles generated with vertical (on the left) and horizontal (on the right) traversals of the same path.

I spent a lot of time on the APIs related to building, storing and iterating over paths. This release has types to make working with simple polygons nicer, as well as utilities to create custom path data structures which work with the tessellators.

What's the catch?

There are few caveats that I want to mention:

- The old fill tessellator was able to provide normals at each vertex. The new tessellator, however, cannot do that. Removing normals allowed a great deal of much needed simplification. I don't think that I will add this feature back. The stroke tessellator still has vertex normals, though.

- The new tessellator is a bit slower than the old one. This is mostly due to not having spent a lot of time profiling and optimizing yet and I am pretty confident that most of the gap can be closed. The new implementation is still about 50% faster than libtess2 (which I consider to be the "industry standard") on the workloads I compared them against (mostly the Rust logo and GhostScript tiger), so it's still pretty decent.

- A lot of APIs have changed. If you've used lyon before it'll still be familiar but updating, while not difficult, is likely to take a bit of effort.

In previous blog posts I mentioned a plan to handle bézier curves directly in the tessellator in order to allow resolution-independent tessellations and handle curves on the GPU (using tessellation or fragment shaders). I had to scope the project down in order to finally get something to shippable and this feature didn't make it. It's possible that I'll revisit it some time in the future, but realistically it will take a long time before I get an ambitious feature such as this one to work, if I ever do.

What's next?

For a little while, bug fixes and polish, after which I am hoping to tag a symbolic 1.0 release some time in 2020. I still have this project of improving the quality of the tessellated geometry (generating less thin triangles) that I would like to get back to, and There are a few algorithms I'd like to play with, like stroke-to-fill conversion and boolean operations.

I would also like to spend some time working with lyon rather than only on it, though I don't know yet what will come out of that.

Conclusion

I am really happy and proud to finally release the new tessellator. It adds up to an enormous amount of work over the last two years, but I think that it was necessary to take the tessellator from pretty good to really robust and reliable. While uncompromising robustness was the main motivation behind this rewrite, a number of important features were also made possible.

Although the rewrite wasn't well set up for external contributions, development didn't stop on the master branch! I would like to thank everyone who made contributions to lyon in 2019 and the years before. Also many thanks to everyone who reported bugs, for their time, patience and support.

This blog does not have a comments section, discussion on reddit.