This is the second part of a series about the talk I gave at RustFest Paris about lyon, a crate that helps you render vector graphics on the GPU in Rust.

The recordings can be found here or on YouTube if you prefer.

Previous episode:

The problem

Screens tend to have a lot of pixels these days.

To the point that when rendering interesting vector graphics (or rendering anything, really) at a high resolution, the per-pixel work adds up and becomes a real challenge for the CPU to process sequentially. Our goal here is to render complex vector graphics at interactive frame rates (This typically means a 16ms budget per frame) and we'd obviously like to have some processing power left to do other things.

Filling paths on the CPU

I am going to use the term "rasterization" and "rasterizer" quite a bit in this post. Rasterization, in a nutshell, is the action of turning vector graphics into raster graphics. In other words it's taking vector graphics and rendering them into pixels. I'll focus on filling paths which is probably the most common primitive, but it's not the only thing vector graphics are made of.

What's the deal with GPUs, anyway? I have a beefy CPU, isn't that enough?

Because images are usually laid out in memory row by row in a contiguous buffer, it's ideal to fill shapes from top to bottom, row after row to maximize cache locality of memory accesses and help the CPU's prefetcher. So it comes without surprise that most path filling implementations use sweep-line algorithms. The general idea is to start with a list of the path's edges sorted from top to bottom. Imagine an imaginary line (the sweep-line) that traverses the output image a row of pixels at a time. We maintain another list, this one containing the edges that intersect the current row, sorted from left to right (let's call them active edges). During the traversal we use the first sorted list to know which edges to add to the active edge list and when. For each row we go through the active edge list to figure out where to start and stop filling pixels, as well as what to do with pixels that are partially covered.

There are variations around this algorithm. For example some implementations run the algorithm in a single pass while others will first generate a data structure that represents the spans of pixels to fill and then fill the pixels in a second pass.

Sweep-lines are very useful when dealing with a lot of different geometry problems (2D and 3D alike) I think that I'll come back to what I like so much about them in another post (maybe in part 3).

For now if you are interested in knowing more about this stuff I recommend having a look at Skia's scanline rasterization code, or Freetype's. The coding style is different but the overall principle is the same. Oh and since this blog post is written in the context of rustfest, you can check rusttype's rasterizer out too, it's implemented in rust.

There is another approach worth mentioning implemented in font.rs, which involves rendering information about the outline of the shape in an accumulation buffer and using that as input to fill the shape in a single tightly optimized loop over the destination image. Notable about this approach is the simplicity of the main filling loop. It runs the same logic on all pixels inside and outside of the shape with very few branches which is very efficient on modern CPUs, at the expense of going over pixels that are outside the shape. When rendering very small images this trade-off works wonderfully. When rendering at very large resolutions, having a sparse representation to avoid touching pixels outside of the shape begins paying off.

This is a good segue into an important point: There is no optimal one-size-fits-all (or should I say, one-fits-all-sizes!) solution. When filling a small amount of pixels, a lot of time is typically spent computing the anti-aliasing along the edges, while paths that cover lots of pixel tend to put more pressure on memory bandwidth filling the interior.

With lyon I focused on large paths covering many pixels, and I wouldn't advise using lyon to render very small text. In another post in this series I will talk a bit about pathfinder which implements two algorithms: one for small resolutions (typically text), and one for larger paths. I think that there is no way around having dedicated implementations if you want to cover both use cases optimally.

Overdraw

We saw how to figure out which pixels are inside a shape and fill them. From there to a drawing containing hundreds of paths the process is usually to render these paths individually from back to front, so that front-most elements don't get overwritten by the ones behind them. Simple enough, however this means that for drawings that are built upon many shapes stacked on top of one another like the famous GhostScript tiger, pixels will typically get written to many times. It's quite a shame, because it means that hidden parts add to the rendering cost just as much as the rest even though they do not contribute to the final image.

The image above gives an idea of the overdraw for the GhostScript tiger. The lighter a pixel is, the more times it is written to with a traditional back to front rendering algorithm.

Where overdraw really hurts is usually memory bandwidth. Unfortunately hammering memory tends to make every thing else slower as well. The other threads end up sitting around waiting for memory which limits parallelism, and after the algorithm is done running, other code will typically run into cold caches. It is very hard to avoid this cost in the context of rasterizing 2D graphics on the CPU (in the best case scenario we have to touch every pixel at least once which is already quite a lot). I have to mention a very cool technique that helps a lot here: the "full-scene rasterizer" approach which consists in having a single sweep-line that renders all paths at once and therefore can touch pixels only once. The rumor has it that the Flash runtime has such an implementation. See also Jeff Muizelaar's full-scene rasterizer which is open-source. This is however quite hard to implement.

What about games?

So how do games manage to render so much complex content at interactive frame rates? For a large part the answer is that games almost always use the GPU for graphics tasks. GPU's have been historically designed and optimized specifically for the needs of the games industry. It would be great if we could leverage these hardware level optimizations when working with 2D content.

Now saying that something's going to be fast because it uses the GPU is certainly not enough. It is very easy to do slow things with a GPU, especially when trying to port CPU code over. Rather than try to adapt a CPU algorithm to the GPU let's try to reformulate our 2D rendering problem in a way that corresponds to the type of inputs GPUs typically get.

The vast majority of 3D content in interactive applications is made of triangle meshes. The GPU has dedicated hardware for dealing with triangles which makes this primitive very appealing for us. Perhaps if we turn vector shapes into flat triangle meshes (conceptually like a 3D mesh with z = 0) we can get somewhere, and that's the direction I took with lyon. There are other approaches to rendering vector graphics on the GPU. As I mentioned earlier I don't believe in a one-size-fits-all solution, however I am pretty confident about geometry-based approaches (leveraging the triangle rasterizer) for the use cases I care most about.

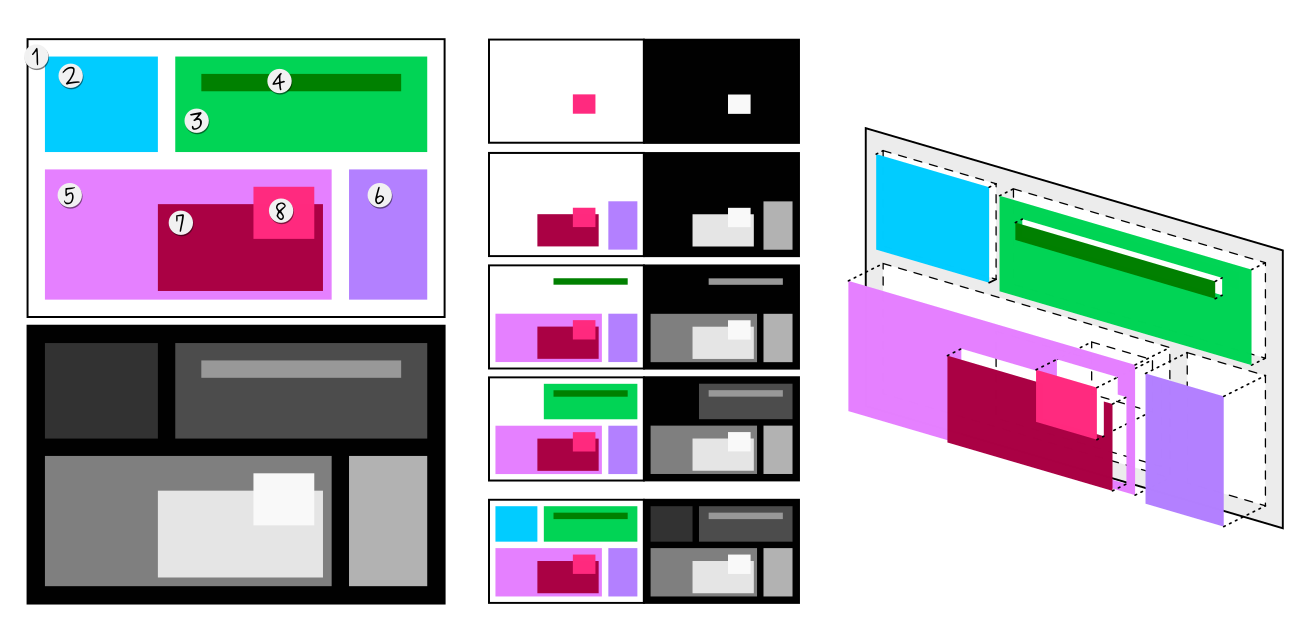

Another interesting feature of the GPU's rasterization pipeline is the depth buffer which contains the depth of each pixel in screen-space. This allows games to render opaque objects in any order and reject pixels that are further behind if something closer to the viewer has already been rendered at that location. This is a convenient trick for correctness but it is also a great tool to reduce memory bandwidth, since by rendering opaque objects front to back, one can minimize the amount of time pixels are written to and greatly reduce memory bandwidth (remember that memory bandwidth was a big issue for CPU rasterization). Transparent objects are then rendered back to front since painting order actually matters for them.

The illustration above was not in the rustfest presentation but perhaps it will help understanding what I am getting at with the depth buffer savings. This is a trick we use in WebRender that consists in rendering opaque shapes in front to back order with the depth buffer enabled to avoid touching pixels many times. The memory bandwidth savings are actually greater than they seem thanks to smart optimizations implemented in the hardware that allow it to quickly discard entire blocks of pixels at a time before computing their color and writing them to memory.

Rendering 2D graphics like a 3D game

Lyon in it's current state is not a 2D rendering engine. It is mainly a way to take vector graphics primitives such as paths, and turn them into triangle meshes in a format that is straightforward to render on the GPU (but lyon doesn't implement the GPU bits at this point). The process of turning paths into triangle meshes is called tessellation (some also use the word triangulation).

If there is a beautiful thing about leveraging the GPU's triangle rasterization pipeline, is that since rendering becomes similar to a video game, we can use the graphics hardware exactly the way it has been meant to be used and benefit from many years of rendering tricks and optimizations from the games industry.

The front to back depth buffer trick I mentioned earlier is not actually something implemented in lyon. It is just a very common optimization in 3D game engines which applies naturally when rendering paths tessellated using lyon. It is also a technique we use in webrender to great effects, and (spoiler alert) it's also pathfinder's most significant optimization for large paths.

This is only one of the many tricks that we can learn from games. Game developers have come up with interesting approaches to anti-aliasing, various graphics effects, animation, handling thousands of individual objects and many more challenges which we can apply to our own needs.

À suivre...

This was part two. We had a superficial look at 2D rendering on the CPU and I argued that there are some benefits to picking a games-like approach to rendering on the GPU. In the next post we will delve into lyon's tessellation algorithm itself.